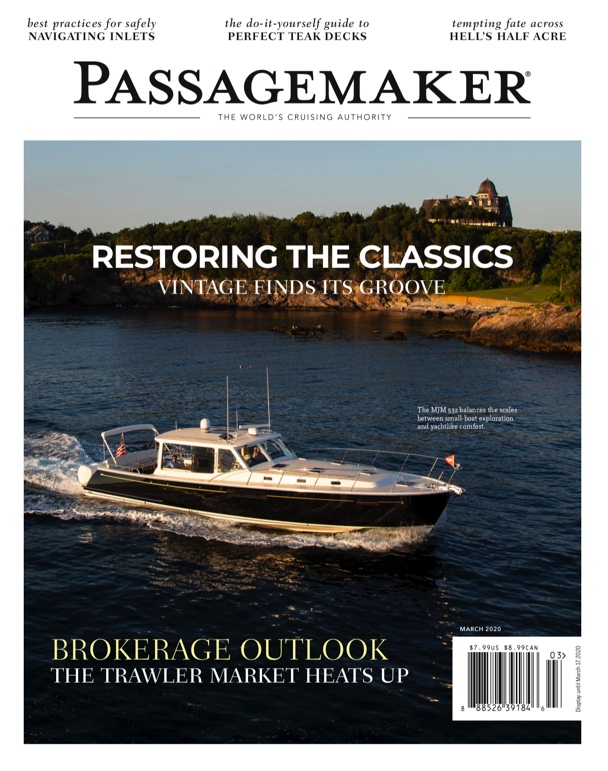

It’s almost 10 a.m. and the 12 Metres have headed out to the racecourse for the third day of the 2019 World Champion- ships. Except for a lone tender, the docks at Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, are empty. Then, MJM Yachts CEO Bob Johnstone pulls up in Breeze, the builder’s first 53z and the company’s new flagship. The day before, a lack of wind had delayed the races and caused Bob and his wife, Mary, to spend 10 hours on the water. Mary, an expert boater in her own right, is taking the day off from racing to find herself a dress for tonight’s 12 Metre social event at Marble House mansion. So, Bob is alone. Breeze already has fenders over her starboard side.

It looks like Bob’s going to back in and execute a reverse 90-degree turn in tight quarters. But instead, he enters bow first and noses the 53z right up to the black RIB at the inside corner. With about 5 feet of spare operating room, Bob jockeys Breeze’s 56-foot-long hull back and forth until her stern clears the tip of dock 7B. Then, he backs her into the slip. He brings her in close enough so the dockhand can grab the sternline without having to bend over, and then brings the bow in so I can grab the bowline. l tie it off, and as I finish making up the springline, Bob’s already standing next to me. His docking maneuver would have put me in a cold sweat, but he looks as fresh as a daisy.

Wearing an oxford, khaki shorts, brown leather boat shoes, a 12 Metre World Championship baseball cap, aviators and an easy smile, the man who co-founded the J/Boat sailing empire in 1977 and founded MJM Yachts in 2002 looks and acts much younger than his 85 years.

Soon, Breeze’s other passengers arrive. The MJM 53z is the official boat of the international jury for the 12 Metre Worlds, and for the third of five days, Bob will take the judges and guests out to the racecourse. In all, 14 people board Breeze. The cockpit and cabin easily accommodate everyone. Using the joystick, Bob takes Breeze off the dock and heads for the Newport Bridge. The boat has air conditioning, but the wind is blowing about 12 knots, so Bob pushes a button to open the three powered windshields. Gobs of fresh air pour in as we head up Narragansett Bay.

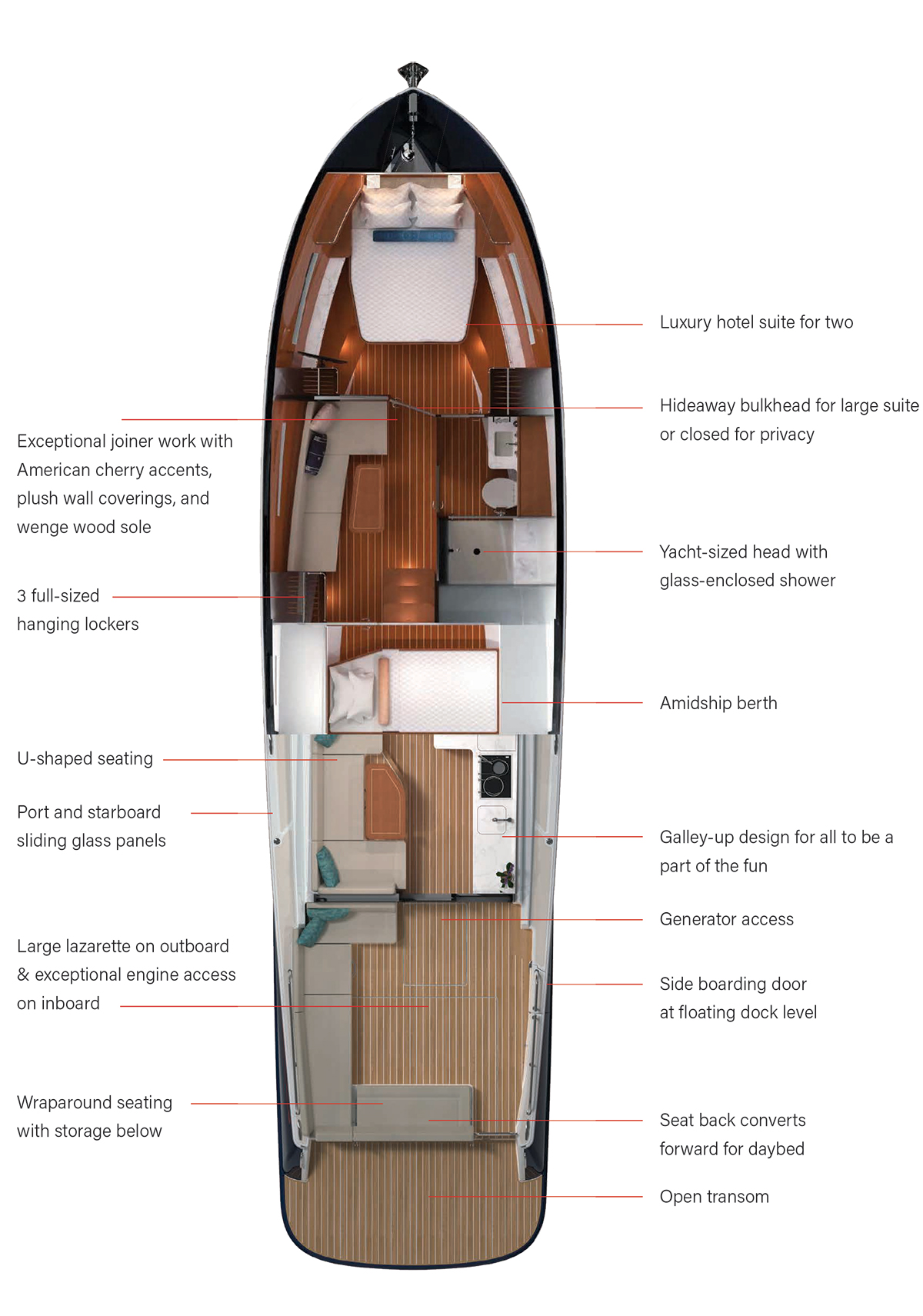

The 53z is MJM’s third outboard-powered express cruiser model, and the largest to date. She is based on the Doug Zurn-designed, inboard-powered 50z hull released in 2014. But unlike the 50z, which has a great room below that con- verts to a second cabin, the 53z has a permanent dual-master stateroom layout. The engine room that housed the triple Volvo Pentas on the 50z is used for extra fuel storage and stowage on the 53z.

The master stateroom in the bow has two portlights, a hatch, a porthole, hanging lockers, a 78-by-60-inch island berth and a desk/dressing table with a comfy seat. The room is spacious and bright. The second stateroom, to starboard, has a 76-by-53-inch berth, a built-in seat and a large panoramic portlight. There are two heads, each with glass walls to separate the showers.

The moderately sized galley to port has a ceramic induction two-burner stovetop, sink, microwave, two-drawer fridge and top-loading freezer. The joints on the natural cherry cabinetry are tight. The seats are covered in off-white Brisa Ultraleather. It’s all simple, tasteful and classic. We pass beneath the Newport Bridge, and Bob pushes the throttles forward. Despite the human cargo—there’s more than a metric ton of people on board—the optional quad 400-hp Mercury Verados quickly take Breeze to 40 knots. (With five people and full fuel, MJM reports a top speed over 44 knots.)

The water is almost flat. On the stern, Ann Conner, who saw her first 12 Metre America’s Cup in 1964, casually flips through a magazine like she’s sitting on her living room couch. She came to Newport in 1961, just three years after the New York Yacht Club moved the America’s Cup to this sailing mecca and switched the competition from the J class to 12 Metres. Her husband, Robert, was on the race committee for the ’74, ’77 and ’80 America’s Cups, and they became friends with Baron Bich, the French ball-point pen magnate who spent 11 years trying to win sailing’s biggest prize.

The MJM 53z served as the official boat of the international jury for the 2019 12 Metre World Championships in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1983, Dennis Conner lost the cup and with it Newport lost its starring role. The America’s Cup stopped using 12 Metres in 1988 and soon the class fell on hard times. This year’s 12 Metre World Championship, the first in Newport since 2009, doesn’t just celebrate a revival for the class. There are 21 Twelves in attendance—a North American record—but for many people, the event is a reunion as well. Sitting on the stern next to Ann is Barbara Lloyd, who covered the America’s Cup for The Newport Daily News, The Providence Journal-Bulletin and The New York Times from the 1970s until the early part of the 21st century. Even “Captain Outrageous,” 80-year-old Ted Turner, who won the Auld Mug on Courageous (US-26) in 1977 and is arguably the most colorful character ever to steer a 12 Metre, has come to town for the Worlds competition.

One of Breeze’s passengers mentions that the average age of the crew on Defender (US-33) must be between 60 and 65 years. Mauro Pelaschier, who helmed Azzurra (I-4) for Italy in the 1983 America’s Cup, has returned to skipper Nyala (US-12) at age 70, and many of his Azzurra crew have joined him. The tactician on Courageous, the Twelve that successfully defended the America’s Cup in 1974 and 1977, is Gary Jobson. He was Turner’s tac- tician in 1977. Back then, Jobson was 26. At this race, he’s 68. He’s joined by three sailors who also sailed on Courageous in ’74 and ’77. Many of the Twelves are loaded with older veterans of 12 Metre America’s Cup campaigns, but all the boats are supplemented with younger blood to work the coffee grinders that sheet in the large sails.

As we approach the starting line, Bob asks me to take the wheel so he can close a hatch. There’s nothing I’d like more than to zip around in Bob’s new $2.2 million baby, but not while Twelves are converging on us from every point of the compass. I steer clear of trouble, and when Bob returns, I happily hand the wheel back to him. He takes us past the race committee boat, the beautiful 1964 motoryacht Serena, and stations Breeze at the other end of the line to await the start of the first race.

There, our view is obscured by photo boats. The judges on Breeze need a clear line of sight, so Bob opens the starboard-side window and lets out a short whistle. The photographers and their drivers look up, and Bob uses his index finger to point where they should move. They try to ignore him, but Bob whistles and points again, and like kids who’ve been caught with their hands in the cookie jar, they move.

The first division of Twelves takes off, and the others follow in a rolling start. To create a level playing field, boats compete against ones that are closest in age while still conforming to the international design rule of their time. The 12 Metre name is not a reference to the boats’ lengths, which vary from 65 to 70 feet; instead, it is a formula that changed with time and that uses boat length, sail area and other measurements to arrive at an equation that totals 12 meters or less.

The 12 Metre class has a long history, dating back to 1907, and Twelves were used in early Olympic sailing events. There are four official divisions: Grand Prix, Modern, Traditional and Vintage. This year, a fifth division, 12 Metre Spirit, was added for two Twelves that no longer conform to a 12 Metre formula, but they will not be eligible for a World Championship title.

The entry list for these Worlds reads like a history of the America’s Cup. The only two Twelves to successfully defend the title twice—Courageous and Intrepid—are here. So are the 1980 America’s Cup winner Freedom (US-30) and the 1958 winner Columbia (US-16).

Patrizio Bertelli, the CEO of Prada and the only Italian in the America’s Cup Hall of Fame, has brought the 1938 Nyala and the 1985-built Kookaburra II (KA-12). Many of the Twelves are based in the United States, but six countries are represented, including Denmark, Finland, Italy, Norway and Canada. Some Twelves were shipped from overseas. Others have been chartered for the competition.

There are four wooden prewar Twelves. The 1933 Vema III (N-11) from Norway and the Finnish-owned 1937 Blue Marlin (F-1) are entered in the Vintage division with Nyala. They’re joined by Onawa (US-6), the oldest surviving U.S. 12 Metre and the oldest boat in the competition. Built in 1928, she was restored in 2000 but still has her original stainless sinks. Her interior looks like a time machine.

The three “plastic fantastics” are also here. The only fiberglass Twelves ever built, Kiwi Magic (KZ-7), Legacy (KZ-5) and New Zealand (KZ-3), shocked the wing-keeled aluminum Twelves of the late 1980s. At the 1987 America’s Cup in Fremantle, Australia, Kiwi Magic gave Dennis Conner conniptions, and at one point he accused the New Zealanders of cheating because they used fiberglass instead of aluminum. He had reason to be fearful: Kiwi Magic won 37 of her first 38 races, but Conner beat her 4-1 in the challenger finals and then reclaimed the America’s Cup against the Australians. That would be the last time 12 Metres would be used for the America’s Cup.

Aboard Breeze, after watching three division starts, Bob bring us upwind to observe the competition. His J/Boat and racing experience come in handy. He knows exactly where he can go to get us close to the action but not interfere with the competition. Ann Conner and the other passengers who experienced the glory days of 12 Metre America’s Cup racing soak it all up. She sailed on some of the Twelves that are now sailing right by Breeze. “What incredible boats they are,” she says. “This brings back a lot of good memories.” At the end of downwind runs, the crews drop the spinnakers, the boats turn upwind and the winches are used to sheet in the main and jib. The sound is frightening. The Twelves groan as the jibs are hauled in and the ends of the booms are winched down hard. There’s a lot of close action, but all the divisions finish the first set of races without incident.

At the downwind finish line, Bob uses Breeze’s Skyhook feature to hold the boat in a stationary position. The four outboards all move independently of one another to hold the boat in the same spot. It looks like the engines have gone haywire, but Skyhook works beautifully. Between races, we eat lunch as 12 Metres zip by us from all directions. Breeze’s Seakeeper gyrostabilizer, a standard feature, keeps her from rolling. Legacy passes so close to our stern, I wonder if her helmsman is aware that Breeze has four outboards hanging there. Legacy’s crew smiles. They think it’s fun, and everyone on Breeze whips out their cameras and smartphones to get a shot of it. The afternoon races bring real drama. On a downwind run, Onawa’s wooden boom sweeps across the deck and knocks one of her crew into the drink.

Left to right: Quad 400 hp Mercurys drive the MJM 53z; Bob Johnstone at the helm of his new flagship; the crew on Finland’s Blue Marlin gets ready to hoist the spinnaker.

Onawa’s crew immediately drops their kite, but by now the Twelve is far downwind and nobody can see the missing sailor. Like many of the competitors, he’s not wearing a lifejacket. A VHF radio call goes out, and safety boats race to the scene. Minutes pass. One of Onawa’s owners is aboard Breeze. He is outwardly calm, but the situation is tense. We are too far away to see if the sailor is conscious at the surface, or unconscious and beneath it. Then, a photographer spots the sailor through her telephoto lens. He is retrieved and reported to be OK. When all the Twelves have finished their second race, Bob points Breeze back toward Newport. “That was fun, wasn’t it?” he says. “We were right in the thick of it. Bob’s certain that Mary has found a new gown for that evening’s big social event, but he has to get himself and his guests back to land so they don’t miss the black-tie dinner dance. “Now,” he says, “it’s our turn to win the race.” He hits the throttles, Breeze takes off, and with an impish smile, he adds, “It’s time to win the hoist.”

Norway’s Vema III was built in 1933. She was designed by famed yacht designer Johan Anker.